By Harlan Chapman-Green

It has been my absolute pleasure to wear on my wrist the latest and greatest from the tiny manufacture of Ferdinand Berthoud. Unveiled at SIHH earlier this year, the imaginatively named FB 1R.6-1 (I’m going to shorten that to FB for this review) is an excellent and utterly unique timepiece in the world of watches. The design is so non-standard that it divides watch experts all the time. I happen to love it, and after the long two weeks, I believe I’m able to tell you why you’d like it too.

Before we begin, let’s start ourselves off with a little history lesson. Born in the Canton of Neuchâtel in 1727, Ferdinand Berthoud was both a scientist and a horologist after being shown the art when he was 14. At the age of 18, he moved to Paris where he continued his work to become a master of the art. Later on, in 1752, Ferdinand Berthoud who was now 25, submitted an equation clock that marked out leap years to the French Royal Academy of Sciences, which was delighted with his work. One year later, Ferdinand Berthoud was given the title of Master Watchmaker by order of the King’s Council.

However, it wasn’t until 1760 that Berthoud would begin to mention sea clocks, and he finished his first in 1761. Like in England at the time, France was also offering a hefty reward to anyone who could accurately determine the East-West position of a boat at sea. You might entertain fantasies about a race between the nations, with France championing the Swiss-born Berthoud and England supporting John Harrison. This was not the case, when the King of France selected Berthoud to examine Harrison’s H4 chronometer, Harrison grumpily denied the request. However, while in London he was appointed as a ‘Foreign Associate Member’ of the Royal Society. In 1765 he would present Marine Clock numbers 2 and 3.

In 1770, Berthoud received the title of ‘Watchmaker-Mechanic to the King and to (sic) the Navy’, he also received a commission for 20 longitude clocks after the success of his earlier pieces. Three years later he would publish “Traité des horloges marines contenant la théorie, la construction, la main-d’œuvre de ces machines et la manière de les éprouver, pour parvenir par leur moyen, à la rectification des cartes marines et à la détermination des longitudes en mer”. Translated, this meant ‘Treatise on marine clocks containing the theory, construction and labour for these machines and the method for testing them for use in correcting nautical charts and determining longitude at sea’, it described all the elements needed to make a marine clock.

In 1785, Berthoud presented his clocks numbered 18 and 19 which were weight powered, and XXV, XXVII and XXIX all of which were spring powered. These were to be used on the fateful journey aboard ‘L’Astrolabe’ which was to continue the explorations of Englishman James Cook. Unfortunately, the ship was wrecked off the Soloman Islands and all the clocks, along with most of the crew, were lost. By this point, Ferdinand Berthoud had enlisted the assistance of his nephew Pierre-Louis Berthoud who was also recognised for his original works. Despite his work for the Royal family and Royal courts, Ferdinand Berthoud was awarded the title of ‘Knight of the Legion of Honour’ by none other than Napoleon Bonaparte in 1804. Three years later Berthoud would pass away at the age of 80 having had no children and was buried in Groslay in the Val d’Oise department. He has been described as one of the most important and influential watchmakers to have ever lived, and yet not many knew much about him, even myself. If I had to go back and re-write my Top 5 Most Important Historical Horologists article, I would probably replace Adolph Lange with Ferdinand Berthoud (nothing personal of course).

Perhaps what was so great about Berthoud was that he is the only known watchmaker to publish the results of all of his research in a detailed and easy to follow manner, meaning all of his experiments could be recreated. He also left behind lots of clocks, tools and equipment, as well as over 4000 pages of published works.

One of the co-presidents of Chopard recently revived the name Ferdinand Berthoud, Mr Karl Friedrich-Scheufele, who wanted to pay tribute to the master himself as well as ‘exalt the very essence and inherent fascination of the watchmaking art’.

The inspiration for this watch is therefore apparent, marine chronometers were often presented in square wooden boxes, in order to be different, the designers decided that if they were to cut the squared corners, to make an octagon, they would have an unusual and interesting case shape. Although certain other manufacturers also use this case shape for their watches, it is fair to say that hardly any of their watches are as interesting, unique or as well executed as the FB is. Don’t take that to heart; this is just horology at its finest.

The FB is a surprisingly wearable watch, though the Masthead found the watch to be a bit uncomfortable when he tried it on in January, I had no such trouble over the two weeks that it was in my possession. Granted, it’s not the most comfortable wristwatch I’ve ever worn, but for a 44mm wide octagonal block of stainless steel, I’ve certainly worn a lot worse. Oh yeah, that’s right, the first quirk of this watch is that the case is made of stainless steel, not white gold or platinum or even tantalum, just straight up steel. Well, almost, this steel has undergone a special chemical treatment, which Ferdinand Berthoud isn’t talking about, that ramps up the hardness of the case to 1200 Vickers, by the way, that steel sports Rolex you’re probably wearing with 904L steel has a Vickers hardness rating of just under 500 Vickers.

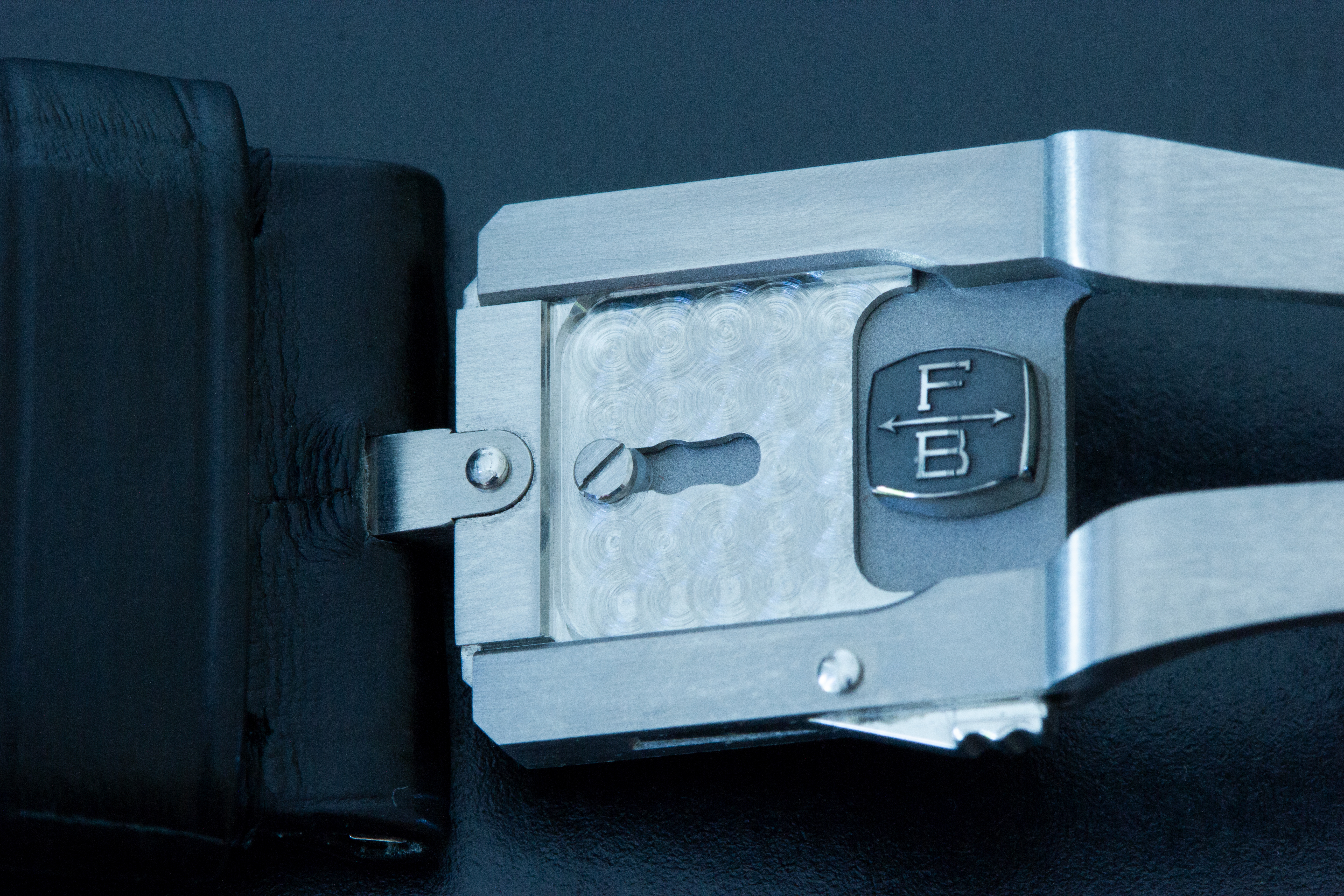

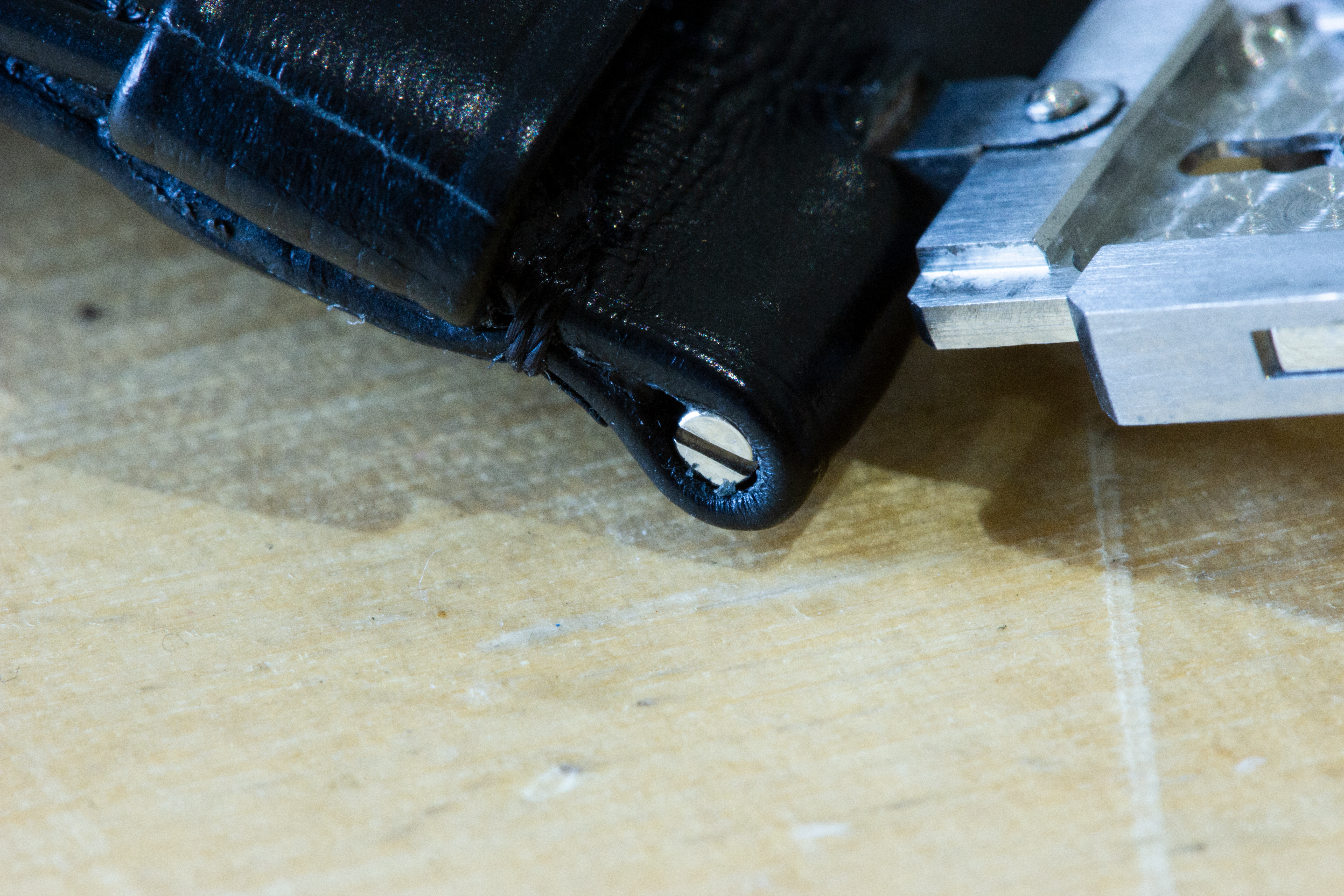

So, it’s a practical dress watch then? Almost, it’s presented on a fantastic hand-sewn black leather strap. This strap has alligator leather on both sides. The reason for this is, once again, practicality, calfskin leather is very sensitive to moisture and may be affected by sweat. However, alligator leather is not as moisture sensitive, and when worn in it become very supple as well so it won’t make your wrist hurt. Connected to this strap is one of the most elegant folding clasps I’ve ever seen. There’s engine turning in the middle of it where most other companies leave it plain; there’s also a little FB logo on a raised part and even a micro-adjuster which allows for an extra millimetre or two, perfect for this hot weather the UK is having. It feels solid and sturdy, none of this light so-called ‘luxury’ feeling which to me usually feels flimsy (I’m looking at you, Patek). The clasp is also a twin trigger clasp, meaning you need to push both sides of it to unlock. Also from the side it almost seems to resemble a link in a chain, we’ll come to that later.

The dial is very clean and well finished. Looking at the press photos of the watch you’d think that it is deep grey, nearing black, however, it is a lot brighter than you’d expect thanks to the vertical satin brushing going on. This watch is in a regulator format. However, for me, it is the wrong layout, the solid bronze hand in the middle is the seconds, while the minutes are displayed via an 18K blued gold hand at 12 O’clock. I feel it should be the other way around. I had a hard time making out the minutes hand since behind it has been cut away so you can see the centre wheel behind it. Some beautiful triangular guilloché work makes it look like there’s many gears there, but it also makes it hard to see the hand. For easy legibility these two should be switched, I ended up looking at the position of the hours to roughly work out the minutes.

Speaking of, the hours are presented in an unusual way. Instead of another subdial, there is a sapphire crystal disk which rotates one revolution every 12 hours. Engraved and then printed in black are the hour numerals in the same Ferdinand Berthoud font as the rest of the watch. This leads to a very minimalist approach to the dial, which is appreciated given the intricacy of the octagonal case, stepped bezel and bubble sapphire crystal. Opposite the hours is the power reserve hand which needs a bit of thinking time. The power reserve is 53 hours, but the reserve only shows zero, one half and one, so you need to halve 53 every time your watch dips to the halfway mark.

Having said all that, this is the most intricate power reserve mechanism out there I’m sure of it. On the reverse side is a truncated cone which has been given an impeccable polish (it’s quite hard to photograph when in the case). As the barrel is wound that cone moves up and down. Resting against it and held in place by a spring is a polished feeler arm which has a jewelled tip. As the cone moves up and down it moves the arm which transmits a signal through the metal. Using ‘complex mathematical equations’, some of which are displayed dial side, this translates the up and down motion of the cone into in and out movement of the arm, which is then translated into left and right on the dial. Confusing? Yes, but definitely awesome. I also like the silver seconds chapter ring running under the bezel which gives the watch just that little bit of lightness it needed to keep the dial from being gloomy. The exposed and polished dial screws give it a more technical appearance, this is no ordinary watch. On the dial there are engraved words, ‘Chronomètre’ meaning chronometer, as this watch is a COSC certified watch. There’s also ‘Val-de-Travers’ and ‘Suisse’ which is the manufacture location, they’re all in the Ferdinand Berthoud font for continuity.

When you first look at the movement, you’ll find your breath catches in your throat. On the back is the beautiful FB-T.FC.R calibre, which lacks the hallmarks of traditional Swiss watchmaking, such as stripes and a conservative finish, and instead goes for something more opulent and technical.

Your eyes are immediately drawn to the tourbillon cage (how could they not be? It’s 16.55mm in diameter), it’s substantial for a tourbillon, showing off 67 individual components flying around and around inside a titanium carriage. There are gold counterweights on the balance wheel and two 18K gold inertia blocks which balance out the escapement assembly. Every single one of these parts is finished to perfection, even the tops of the pins holding in the gold weights on the wheel. It’s not a flying tourbillon, though, but the polished arm which holds it in place can fool you into thinking that it is a part of the carriage.

Moving clockwise, the power reserve assembly I mentioned earlier is sat next to the tourbillon and can be viewed from the top and the side as there isn’t a solid divider between them. Move around still and you come to one of the best parts. This watch uses a fusée and chain mechanism to supply power, y’know, like Richard Langes and Breguets and whatnot. Older than the balance wheel itself, the fusée and chain are made of a fusée (the cone), a barrel and a chain. That chain is made up of 474 links and over 300 pins, all of which must be painstakingly decorated before being put together, the diameter of one of the pins is 0.3mm. The chain is 28cm long and can support up to three kilograms of tension, not bad for a tiny little chain. Mind you, it’s perhaps not as advanced as the chains found in Romain Jerome watches which often use jewels instead of traditional pins, but we’ll let this one off because it’s so well finished. The differential gear is of an ‘unusual design’ which means, well, we don’t know really, there’s nothing else about it to say how that’s an improvement. The ratchet which stops the barrel going backwards during winding is located at 12 O’clock and has a high polish to it. The fusée, chain and barrel are easiest to see through the two small windows on the case sides.

Finally, at 9 O’clock is a small cutout with more of that triangular guilloché that we saw underneath the minute hand on the dial. Quite what that’s called we aren’t sure again but do check back as it may be in an edit at the end of the article.

Another unusual feature of the watch is the movement and its layout. It’s one of the only tourbillon watches outside of Patek Philippe and Lange which does not display the tourbillon on the dial (the Datograph Tourbillon springs to mind) that I can think of. That’s not detrimental either, that delays the inevitable excitement of seeing it, which you’ll do a lot unless you are an utterly emotionless collector.

Continuing with the quirkiness, we come to the construction of the movement itself, nearly all but the most technically unusual movements make use of components stacked inside plates and whatnot. However, this watch uses a technique from the 18th century when Berthoud was alive. All the parts are put together as one would expect, then they are sandwiched between a top and bottom plate, which are connected by polished titanium pillars. The movement is then installed upside down in the case so that on the caseback nearly all the components are hanging downwards (except the tourbillon which is connected on both sides, but still facing towards the wrist) when the watch is worn. I had a bit of a chuckle to myself when I held the watch up to a light and was surprised to see the light peeking out between the edge of the movement and the case, whether this is intentional to show off the unusual construction I’m not sure, but it’s certainly something I’ve never seen before.

One of the things I’ve neglected to mention thus far is the crown. It’s unusually large for a dress watch, yet it fits in with the design here. It’s also straightforward to use as well thanks to its diameter, and it operates the time very smoothly. It also serves as a reminder, because when you pull it out, you can see just how tiny and thin the crown stem is, so you must be delicate with it. The watch doesn’t have any kind of hacking or zero reset functions, so the time must only be wound forward, but it does feel buttery smooth. The watch is quiet when winding, but is still quite loud when running normally. I found I could hear it ticking away when I was sat upright checking my laptop, the distance between the watch and my ear was most likely between 35 and 45 centimetres.

I’m sure lots of people are wondering how easy it is to wear, that’s undoubtedly one of the things I look out for when reviewing a watch. Honestly, it’s not great. The retail price of this watch is €198,000, and you feel every single one of those Euros whenever you put it on. That’s not always a bad feeling, in the right setting with the right outfit you do feel like you’ve made it. However, you need to consider that that feeling only happens when you are dressed up. The whole shirt and Wrangler jeans kind of works, but then you need to factor in what you’re going to do, sitting around at home with it made me feel like it was silently judging me while waiting to go to some cocktail party. Not to mention there’s the apprehension of wearing such a highly valued item on your wrist, though any two hundred grand watch will make you feel that way. One slight advantage was knowing the case wouldn’t be scratched just by looking at it.

If I had to give this watch a score out of ten it would be a nine, despite its oddities, some of which make it difficult to wear, it is a shining example of the ingenuity present in the watchmaking industry, well, at least in Val-de-Travers. Everything about this watch has been designed to be complicated and expensive, even the metal parts in the leather strap are held in with polished screws instead of spring pins. Even your very top end manufacturers with higher outputs and broader reputations will struggle to keep up with the amount of detail in this watch. Nothing is left to chance, and no part of it is left untouched, it’s all either functional and finished beautifully, or just finished beautifully and there for the hell of it. Other articles from other sites mention how this can embarrass the pants off of watches that are way more expensive than it with its finish. Wearing this piece of art was an absolute honour, it’s so expensive and so rare (one of twenty) that most will never get to see it. That is perhaps the saddest part, that most will overlook it for a more recognisable piece, or they won’t get to see it at all.

All that oddness combined with rarity is its ultimate downfall as well. I spoke to a London based company which has sold them previously, and they mentioned the difficulty they had in selling these watches. No-one knew about them, and they were nervous about the case shape and design, so they went somewhere else. It’s sad to think of all those Ferdinand Berthoud timepieces sitting around in the window waiting to be bought, but it’s not as sad as all those watch fans who do know the company that will never get to see one at all.

Still, apart from that it’s awesome, that’s what we do, bring you the rarest and coolest watches we can find for a hands-on. For more info, please visit Ferdinand Berthoud online.

Photograph book credit: Watchmaking by Dr George Daniels ISBN: 9780856677045