The United Kingdom’s involvement in horology as we know it today is both profound and under-appreciated. The horological powerhouses currently are Switzerland, Japan, China and Germany, all of which have several brands that dominate the world. But, once upon a time, these guys looked to the United Kingdom and France as the leading lights in precise timekeeping, and although they are not the same dominators they once were, both countries are having a little bit of a horological resurgence. Today, we’re going to look at ten of the most influential horologists to come from the British Isles. We’re guessing there may be a couple of names on this list that even you haven’t come across yet!

To be clear, this is not one of our popular Top 5 articles extended to include ten entries. There is no definitive winner here, nor are the following ranked in order of their contribution. Instead, we use a chronological order.

Richard Towneley (1629 – 1707)

One of the two year-going clocks made by Thomas Tompion, featuring Richard Towneley’s deadbeat seconds. There have been eight people named Richard Towneley, we are not sure of a portrait of this one exists.

Richard Towneley was born in Lancashire in 1629, which puts him first on our list. As you’ll discover with most of the entries on our list, he was interested in multiple subjects that were becoming popular in the 17th century such as mathematics, philosophy and astronomy. Towneley was most notable for his involvement in the creation of Boyle’s Law, which states that assuming the number of molecules and the temperature remains at a constant, there is an inverse relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas. It is believed that Towneley and his family’s physician were both into their experiments, and used a barometer to measure the difference in pressure between sea level and the top of Pendle Hill in Lancashire. They realised that there was a relationship between air density and pressure, and the physician wrote a paper about it which attracted Robert Boyle’s attention, and he would go on to make the draft into a finalised piece that would result in the creation of Boyle’s Law. Apparently, Boyle himself preferred to call it “Mr Towneley’s hypothesis”.

Towneley was also a horologist and is credited with the creation of the deadbeat mechanism, sometime around 1675, (though some attribute it to George Graham due to his use of it in his works from 1715). This deadbeat system eliminated any backlash from the anchor escapement, which could cause timing inaccuracies. This system would be commissioned by Towneley’s close friend Thomas Tompion, more of which follows below. Towneley’s system was clever but was reported to be quite unreliable, but still, it’s the first.

Robert Hooke (1635 – 1703)

Born on the Isle of Wight in 1635, Robert Hooke was not just an influential horologist, but more of an all-round intelligent guy. Like his Dutch rival, Christiaan Huygens, Hooke was interested in multiple fields of study including languages and the making of musical instruments, today we’d call him a polymath. He is probably more notable for his discovery of plant cells through a microscope and the nature of fossilisation than the invention we’re going to talk about.

Most historical records indicate that Hooke was the inventor of both the anchor escapement found in clocks and the balance spring seen in mechanical pocket watches. The anchor escapement is attributed to Hooke through writings from the early 18th century stating it was an “admirable invention of which Dr Hooke, […], was the inventor,” according to Henry Sully. The anchor is a reliable design that forces the escape wheel to turn in one direction only, regulated by a pendulum and thus providing accurate time. Hooke was described as a very intelligent and short-tempered man. When he learned of rival Christiaan Huygens releasing his own design of balance spring, for instance, he was furious and went through archives of meetings he’d had where he showed his work, ripping out the pages that proved he had invented the escapement. These pages wouldn’t be found again until they turned up in 2006 in the cupboard of a home in Hampshire of all places.

Thomas Tompion (1639 – 1713)

Tompion is undoubtedly one of the founding fathers of horology as we know it. Born in Bedfordshire, England, Tompion was known for his extreme levels of craftsmanship, most of which was attributed to the French and Dutch protestants that worked for him during his time who were able to meet his demanding standards. At the foundation of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, a worthwhile journey for any horological enthusiast, Tompion was commissioned by King Charles II to create two clocks that would be extremely accurate, accurate enough to perform astronomical calculations. Tompion had a close relationship with Robert Hooke and used Hooke’s idea of long pendulums making short swings in these clocks, which also used a deadbeat escapement created by Richard Towneley to make them more accurate than a normal clock, these clocks needed rewinding once a year.

Tompion’s relationship with Hooke meant he was able to make use of Hooke’s new balance spring invention, and he immediately became renowned for his pocket watches. It’s believed that Tompion’s workshop made over 5500 pocket watches, and over 600 clocks, during his time, and it’s also believed but never proven that Tompion’s grandfather clocks were the first time a serial numbering system was used for standard manufactured goods. Despite his busy lifestyle, Tompion had plenty of time to teach his art to the next generation. That next generation being his successor, George Graham who would take on Tompion’s business and marry Tompion’s niece.

Joseph Knibb (1640 – 1711)

One of four documented clocks from when Knibb was stationed in Oxford, between 1662 and 1670

Joseph Knibb was born in Oxfordshire in 1640 and had quite a troubled beginning to his career. When he was old enough to set up his own premises for horology inside the limits of St Clement’s in Oxfordshire, he was met with lots of resistance due to him not being attributed the title of ‘freeman of the city’, which basically meant that he was not a valued member of the community or a dignitary either. Although applying twice, he was refused both times but was eventually admitted on the condition that he worked for Trinity College, Oxford, as a gardener. That didn’t stop him.

By around 1670 he had moved to London to set up shop once more and his reputation for high quality and simplistic designs became known. Though there are works signed in Knibb’s name, one from the George Daniels collection sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 for over £1.2m, Knibb was also known to be a master pendulum maker and was known for his intricate decoration of them. Perhaps the most interesting of his works is a complication I hadn’t heard of until researching for this article: the Roman strike. Normally striking watches chime the hours, quarter hours and minutes sequentially, but Roman striking chimes the hours in the same way we think about Roman numerals, as in, they are single digits up to four, then five is represented by a V sign and we add single digits onto V, so eight, for example, becomes ‘five and three’. One bell tone represents one hour, while a lower tone represents five hours. In this way, twelve o’clock would be sounded as two low tones and two high tones, rather than twelve repetitive tones like in modern minute repeaters. This system is designed to save power compared to a normal repeater and was quite intuitive.

Daniel Quare (1649 – 1724)

An elegant brass striking and quarter repeating table clock by Daniel Quare and Stephen Horsemen, circa 1720. We have no record of a portrait of Daniel Quare.

Although it is believed Daniel Quare was born in 1649 and that he grew up in my home county of Somerset, no one can be quite sure due to the lack of record-keeping at the time. We don’t even know who taught him the art of horology, either. What we do know is that, like most of the entries on this list, Quare at some point in history ended up in London, and was admitted to the Clockmaker’s Company based in what is now the City of London in 1671. Quare was highly skilled in both artful decoration and the mechanisms behind it. Though, once again, a lack of records provides firm evidence it is strongly suggested that Quare invented repeating watches. This was challenged in 1687 by another horologist called Edward Booth, operating under the alias Edward Barlow, who claimed that he had invented the rack and snail mechanisms for striking watches.

When the patent was filed by Booth, the Clockmaker’s Company opposed it successfully, stating that Quare had already invented the mechanism for his repeater, which was supposedly more sophisticated than Booth’s. Other notable contributions from Quare include an unusual clock with two pendulums that was placed in the Royal Hospital in Greenwich, which was used for survivors from the Royal Navy. It’s currently open as an attraction to tourists who have also visited to see other sights such as the Royal Observatory and Cutty Sark. A visitor’s guide to the sights of London from 1844 also indicates that in King William III’s bedroom in Hampton Court stood a Daniel Quare clock which needed to be wound once a year, whether it still exists is unknown.

George Graham (1673 – 1751)

Cumberland-born George Graham was, as mentioned above, mentored in the art of horology by none other than English horologer-extraordinaire Thomas Tompion. Working with Tompion, Graham is credited with creating the first modern orrery, a device used to plot the positions of the planets in the solar system. Though this idea is not new, even Ancient Greece had a machine doing this known as the Antikythera mechanism, Graham and Tompion’s design used clockwork to plot the real-time course of the planets. The first orrery was gifted to Charles Boyle, the 4th Earl of Orrery, from which comes the name. This invention might come as a surprise to you, but Graham was very interested in astronomy as well. He made the mural quadrant (a device capable of precisely angling a telescope up to 90 degrees, mounted to a wall and oriented on the meridian) at the Greenwich Royal Observatory which was used by Edmond Halley, the namesake of Halley’s Comet.

Though Graham is credited with the invention of the deadbeat escapement, as we’ve discussed above it was actually an invention made by Richard Towneley for Thomas Tompion, Graham’s mentor. However, Graham did fine-tune the escapement for use over long periods of time and became renowned for it. The deadbeat escapement is still used in watchmaking today as an example of both technical skill and aesthetic design, some cultures prefer a watch with a ticking seconds hand rather than a sweeping one. When John Harrison arrived in London, he was introduced to Graham via Edmond Halley and the two became good acquaintances with Graham giving advice to Harrison on the mechanisms for his famous marine chronometers. Graham also sought more funding for Harrison and spoke on his behalf to the Board of Longitude. Though the current Graham watch brand seeks to use this history in its marketing, it appears to most that there is very little connection between George Graham and the current brand. An example of Graham’s work resides in a museum in Bury St Edmunds in the UK.

John Harrison (1693 – 1776)

Ah, John Harrison. This name was bound to turn up, and with good reason. Born in West Riding of Yorkshire (yes, that is a real name for our overseas readers), Harrison was a self-taught carpenter and horologist and is credited with creating the first successful marine chronometer which would go on to revolutionise sea travel. Harrison was already well underway to success by the age of 20, he made his first grandfather clock at this age, it’s on display at the Science Museum in London alongside his second which was finished two years later. His third resides in Yorkshire. Harrison was commissioned to make a turret clock for Brocklesby Park in Lincolnshire, and his design used a grasshopper escapement (another invention of Harrison’s), incorporated into the wooden movement. As a testament to his design, it’s still in operation today inside the white tower (turret) at the top of the hall.

Though Harrison made a number of high-quality clocks and creative inventions, arguably his most important was the marine chronometer. If you go to the Greenwich Royal Observatory (I’ve mentioned it about a thousand times by now, so you really should go) you’ll be able to see Harrison’s H1 sea clock on display. It might look a little bizarre compared to what you normally assume with timepieces of this era. For starters, there isn’t a pendulum on it, which would be affected by the motions of the boat. Instead, two dumbbells are linked together via a spring. Parts of the clock are made of wood, which performed very well undoubtedly thanks to Harrison’s carpentry skills. Harrison’s H1 clock went with him out to Lisbon and back, despite some trouble on the outward journey it performed exceptionally well aboard HMS Orford. Harrison safely navigated them back, meanwhile, their own calculations which were largely based on dead reckoning, put them over fifty miles out. Harrison worked on several chronometers throughout his life, including two more clocks (though H2 was abandoned due to the design of the balance being affected by the tacking motion of ships) and at least two watches.

Thomas Mudge (1715 – 1794)

Though the name Thomas Mudge isn’t a household name, it is associated with the creation of perhaps the single most revolutionary design ever in the history of horology. This design, in various forms, is still in use to this day and is the backbone of our precious watches. I’m referring to the detached lever escapement. Born in Exeter, Devon, Mudge would spend the first 15 years of his life in the West Country, before being sent to London where he quickly became the apprentice of George Graham. Mudge was found to be very skilled in this department and was recognised for his work on complicated watches by Ferdinand VI of Spain, who we know to have commissioned at least five watches from Mudge. One of his watches, a large gold watch presented by George III to Queen Charlotte still remains in the Royal Collection in Windsor today.

The detached lever escapement changed how watches would be for the rest of time. Unlike previous escapements which relied on a physical connection between the balance wheel and the escapement at all times, the detached lever escapement allowed the balance wheel to swing freely, only coming into contact with the pallet fork when an impulse pin connects the two to push the balance wheel in the opposite direction. Though it seems simplistic to us now, consider that this is simply because nearly every mechanical watch has one. The design has been improved a lot since Mudge’s time, to incorporate high-tech frictionless materials such as silicon, but it’s still kept the same principle. Even inside a tourbillon or carrousel, it’s the same detached lever escapement. The only major step away from this design was taken by Zenith with their Defy Lab watch that did away with an oscillating wheel and lever escapement altogether, but this is hardly a mainstream product for now.

John Arnold (1736 – 1799)

Born in Bodmin, Devon, in 1736, John Arnold is a name most of us are probably familiar with to a degree. There is currently a Swiss firm using his name as Arnold & Son, though whether there is a legitimate connection between Arnold & Son and John Arnold isn’t entirely clear. Arnold caught the attention of astronomers who were looking for someone to replicate John Harrison’s marine chronometers. Unfortunately, reproductions of Harrison’s extremely precise chronometer design took far too long to produce and were very costly. Despite being handed a published work on Harrison’s designs, Arnold couldn’t come up with something that could be easily mass-produced. Instead, he would modify previous designs to improve upon them, one of his patents from 1775 included a new spiral and a helical shaped balance spring which reduced the frequency of random errors that occur with flat balance springs. A later patent in 1782 protected his work further, which had been copied by several horologists including Thomas Earnshaw. The patent concerned the terminal curve, the curve where the balance spring bends towards the centre at the ends. This curve improved accuracy and would be used in nearly every chronometer for over a century.

However, there is perhaps a name that goes alongside Arnold that deserves mention: Breguet. Arnold, who was then the best clockmaker in Europe, was introduced to a Breguet clock in 1792 by the Duke of Orleans. It’s said that Arnold was so impressed by Breguet’s work that he travelled straight to Paris to visit Breguet and asked him to take in his son, John Roger Arnold, as an apprentice. Breguet would later send his own son, Antoine-Louis Breguet, to London to learn from Arnold. An impressed Arnold allowed Breguet to use any of his designs in his watches. This may have come about because he was fed up with other people copying his works. The overcoil, patented in 1782, was used by Breguet and formed the Breguet overcoil, as well as Arnold’s spring-detent escapement. Even the layout for Breguet’s dials using guillocheé dials was incorporated from Arnold’s design to great commercial success. Even today, Breguet is regarded as having the best guilloché dials in the business. One of Arnold’s ideas was to rotate the balance wheel on its own axis to avoid gravity associated errors. Sound familiar? Though Breguet had been toying with the idea, he acknowledged Arnold as the origin for this thought and built his first tourbillon into an Arnold pocket watch, number 11, which was given to Arnold’s son in 1808.

The back of the watch was inscribed “The first Tourbillon timekeeper by Breguet incorporated into one of the first works of Arnold. Breguet’s homage to the revered memory of Arnold, given to his son AD 1808.” It resides in the British Museum.

Edward John Dent (1790 – 1853)

Edward John Dent is, surprisingly, the first Londoner on this list so far. All the other names were born either in the North or the South West of the UK and travelled to London either to learn horology or to set up their own business. The family business at the time revolved around candlemaking, but Dent became fascinated by mechanical clocks and watches as a young teenager. His cousin, Richard Rippon, was an expert watchmaker and took him on board to learn the art, which he was successful at. At the age of 24, he supplied a pocket watch for the Admiralty of the Navy, though he didn’t have much commercial success. Fast forward fourteen years and Dent had landed himself at a place so many of his predecessors had worked, the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. He was a consultant examining and repairing chronometers and apparently charged an enormous fee which was nevertheless coughed up for his work.

In 1830 he learned of a new firm with an opening position working under the name of John Roger Arnold, John Arnold’s son who had learned his trade from Abraham Louis Breguet. Instead of working for Arnold, Dent became a partner in the business and used his experience growing up with a family enterprise to market the firm. Coupled with Dent’s expertise, this left Arnold who was twenty years his senior to tinker and invent while still having a say in the business. The firm became known as Arnold & Dent and was one of the 21 companies to send a chronometer aboard the Second Voyage of the HMS Beagle, which carried a young graduate named Charles Darwin to the Galapagos and received the comment “rather good” from Captain FitzRoy, this was the standard comment.

A frustrating lack of passion to dominate the world of chronometers eventually forced Arnold and Dent to part ways. But, Dent would found his own company, named E.Dent & Co, which would be responsible for building the most famous clock of all time, the clock inside the Elizabeth Tower, next to the Houses of Parliament in London. A clock most mistakenly known as Big Ben, when it is, in fact, the largest bell in the tower with this name. Sadly, Edward John Dent passed away a year before completion and left it to his son to finish. Dent still makes watches today, though they appear to use ETA movements in their interesting case designs. It could be great to see a resurgence from them

Bonus: Charles Frodsham (1810 – 1871)

The second Londoner on this list is Charles Frodsham. He was an apprentice to his father, who was a well-known chronometer maker himself. By the age of 20, he had submitted two chronometers to a competition based in Greenwich, one of which came a respectable second place. He would set up his own business after his marriage to Elizabeth Mill and would take on the Arnold watchmaking business after the death of John Roger Arnold. It would trade as Arnold & Frodsham for thirteen years. Frodsham was very notable not only for his inventive watches but also for his publications surrounding them. Much of his writings to the Astronomer Royal at the time are preserved in the Cambridge University Library. In 1871 he would present The History of the Marine Chronometer, which was the first time something about chronometers on that scale had been written in English.

Frodsham was also a Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, a title held previously by Thomas Tompion, Daniel Quare and John Roger Arnold. He was also a founder of the British Horological Institute. Sadly, he passed away in 1871, the same year The History of the Marine Chronometer was published. His son, Harrison Mill Frodsham would take on the firm after his death, publishing his own material. The Frodsham company kept on working, providing sidereal regulators to observatories in the USA and Australia. Frodsham also specialised in complex tourbillon and carrousel watches that were successful in Observatory trials. The firm went quiet through most of the 20th century, and a small division, which made instruments for the emerging motor industry was formed under the Frodsham name. However, the Frodsham name kept going, and after 16 years of research released its first new watch, the Double Impulse Chronometer Wristwatch, the first watch to use George Daniels’ double impulse design. Charles Frodsham & Co is the oldest chronometer manufacturer to continuously trade, having started in 1834 and never stopped since.

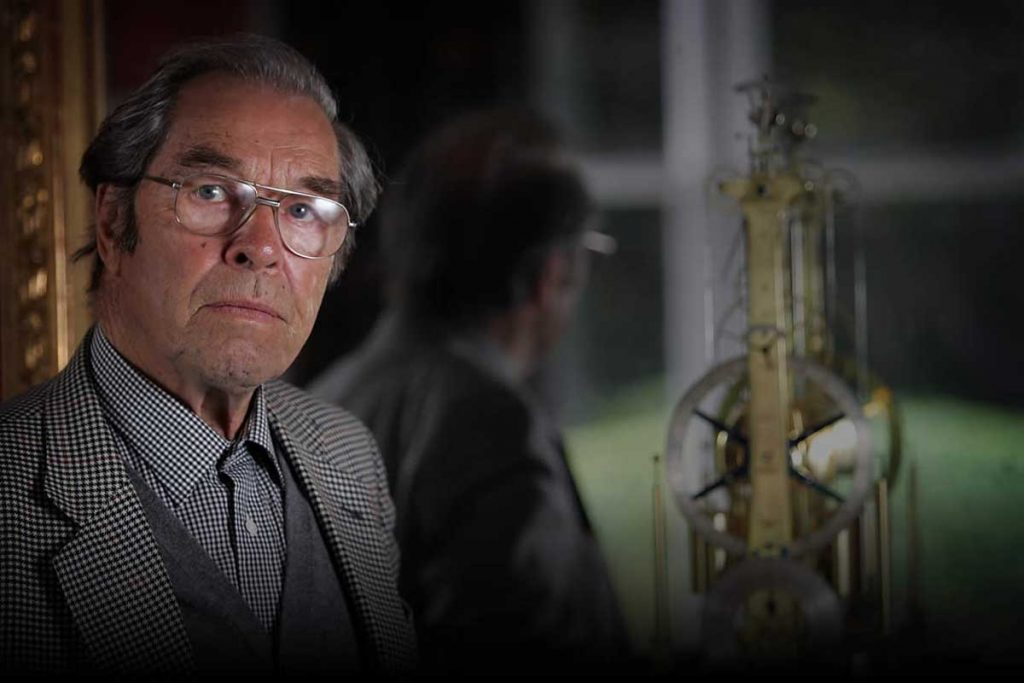

Bonus: George Daniels (1926 – 2011)

I don’t think it’s possible to make a list of Great British Horologists and not even give a mention to the late George Daniels. Born in Sunderland in 1926, Daniels had an interest in watchmaking before he entered service in the Army in 1944, and repaired the watches of some friends there. After leaving the Army two years after the end of WWII, he used the money he had to buy tools and got himself a small job as a repairer of watches, while taking night classes to expand his knowledge. His most notable influence was Abraham Louis Breguet, which is quite evident on Daniels’ works which feature guilloché dials and similar layouts to Breguet.

Daniels became known for making high-end watches, but he only made them for selected customers that he cared about, which made him notable in the high-end watch scene. Daniels is perhaps most notable for inventing the Co-Axial escapement, which removed any rubbing friction from the escapement assembly and thus removed the need for lubricant and regular maintenance. Despite Patek Philippe’s interest in the mechanism, it was Nicholas Hayek, founder and chairman of the Swatch Group that would pick up on the genius of Daniels’ design. In 1999, Omega unveiled its first-ever watch to use the Daniels Co-Axial escapement, an escapement which has been a mainstay of the brand ever since.

Before his passing in 2011, Daniels had time to work with an upcoming independent watchmaker, Roger W Smith, who used Daniels’ book entitled watchmaking as his guide. Daniels turned down Smith’s first attempt at a watch, stating it looked ‘handmade’ rather than ‘created’. Smith’s second watch would gain approval and would prompt Daniels to invite Smith to live on the Isle of Man and collaborate. When Daniels passed away in 2011, he left his entire workshop and all his tools to Smith, who uses them to make his watches and service Daniels timepieces as well.

So, now we’ve seen some of the history of our beloved horology, and we’ve made some discoveries along the way, too. I must confess that this article wasn’t intended to be this long, but every time I researched a prominent figure, it would reveal a connection to someone else who was worth a mention as well!

Where does this leave us in 2019? The UK is starting to see a few names pop up, including Roger W Smith. These include Garrick and Struthers, which are very interesting to me as a native of this land. Hopefully, we may see a resurgence in British watchmaking in the same way Germany did in the 90s.