By Harlan Chapman-Green

Out of all the complications one could put in a watch, the tourbillon is the only constant reminder that one is wearing a timepiece of extraordinary detail and engineering. Granted, both chronographs and minute repeaters alike are also reminders that watchmaking is a tedious and time-consuming drive for innovation. However, these aren’t always running (and in some cases, shouldn’t always be left running anyway). Only the tourbillon is in constant motion to draw the eye, we love calendar watches too, but they don’t move very much.

What I’m going to attempt next is a brief history of this famed complication, one of my favourites. To note, I don’t plan on going very in-depth with the whole argument as to whether a tourbillon in a wristwatch contributes to the accuracy of the said watch. That is an article for another day.

The Problem

Abraham-Louis Breguet

The idea for the tourbillon was dreamt up by horology’s most important figure, the Swiss-born Abraham-Louis Breguet. At the time, Breguet’s watchmaking business was based in the city of Paris, which is where he made most of his timepieces. Breguet was obsessed with practicality, despite his watches being extraordinarily artful and a potent symbol of the Neoclassical arts of the time. One only needs to take a look at some of his prior inventions, such as the Pare Chute (an early device used to protect pivots for the balance wheel), to realise that while Breguet timepieces were very ornate in their details, they were also engineered to the extreme.

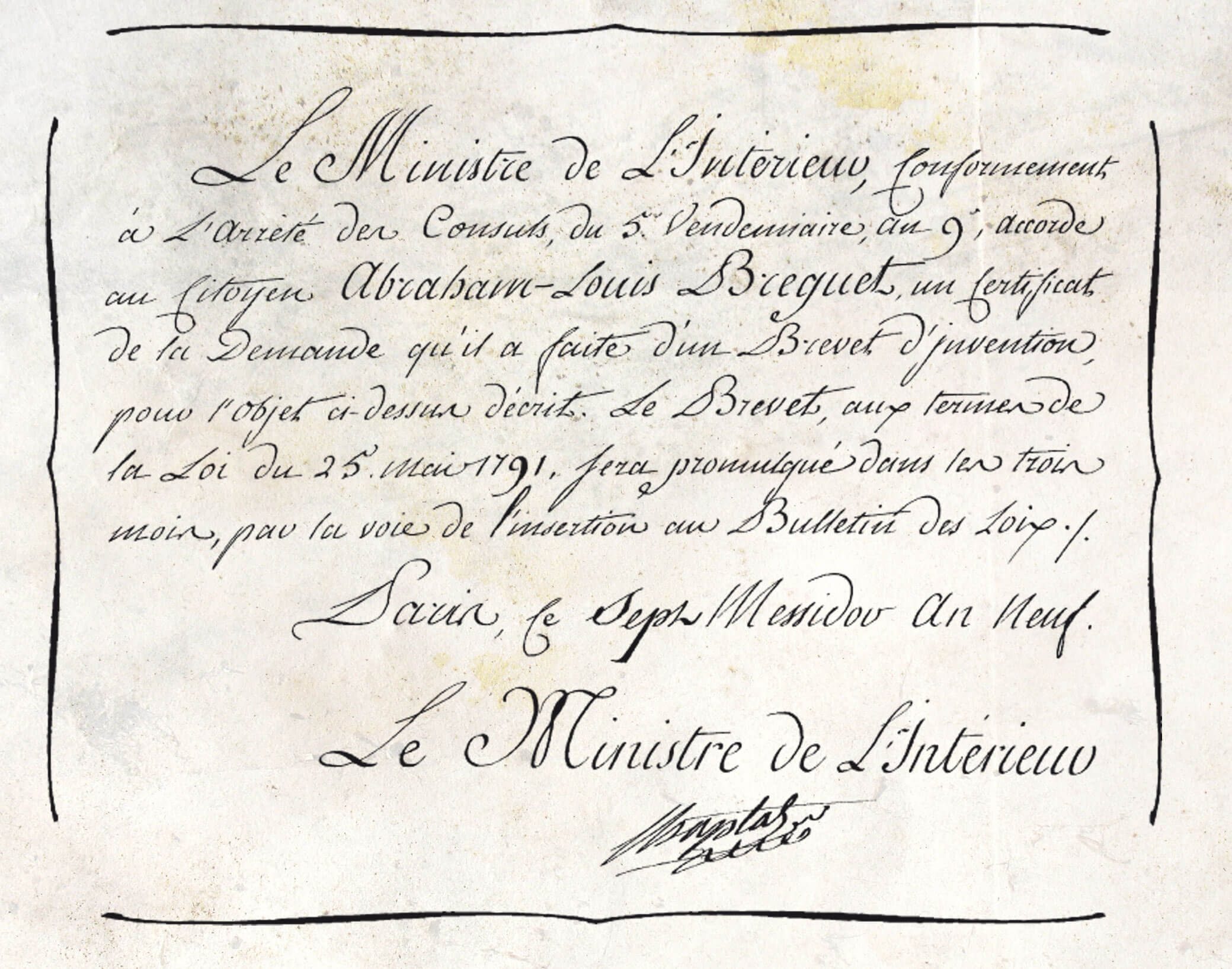

Brevet Du Sept Messidor An Ix

Breguet noticed that the watches of the time all had the same issue, they all came back with uneven wear and tear. The reason for this is simple: apart from being moved around a few times, they spent nearly all of their time held in a vertical position. That’s not a fault of the watch; they were like that because they were pocket watches, as at this time wristwatches hadn’t been invented yet. What this meant, though, is that the distribution of oil and friction between the moving parts was exemplified in some areas, and relatively unaffected in others. That means over time the watch could begin losing or gaining time as the wear increases as time passes. To combat this, Breguet had to think big.

The Solution

The watch n° 169

Enter the tourbillon. An ingenious mechanism designed to counteract the effects of the pull of Earth’s gravity on the oscillating balance of a pocket timepiece. Think of the tourbillon as one thinks of one of Shakespeare’s great plays, such as Hamlet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In those plays, the characters are acting out a play, while also performing the actual play itself (it is a bit confusing when written down, I admit). The tourbillon places an oscillating escapement inside another rotating escapement system. As the balance wheel and subsequent pallet and gears oscillate, they are also turning on the axis. This rotating motion mitigates the uneven wear on the components, as they are all equally exposed to the effects of gravity, increasing accuracy and longevity of the escapement system. The tourbillon really is poetry in motion (sorry, that was bad).

While the tourbillon was developed around 1795, the patent for the device came much later, in 1801. It was a ten-year patent that was issued to the new type of escapement. When translated the patent reads:

“By means of this invention, I have succeeded in cancelling through compensation the anomalies caused by the different positions of the centers of gravity of the regulator movements, to distribute frictions on all parts of the circumference of this regulator’s pivots and of the holes in which these pivots move, so that the oiling of the friction surfaces is always even, in spite of oil coagulation, and finally to cancel many other causes of error influencing movement accuracy, which could only be attained until now by constant trial and error and often even without any certainty of success”.

Breguet’s tourbillon wasn’t entirely operational when that patent was filed, however. Records show that several prototypes were made in this period with varying success. One piece, No.169, was gifted to one of Breguet’s closest friends, an Englishman named John Arnold, the namesake of Arnold & Son watches. While Breguet only made 35 examples of the tourbillon between 1805 and the year of his death, 1823, Breguet tourbillons were highly prized by the aristocracy for their vast complexity and their rarity. One such example was a curious Breguet clock, acquired by the Prince Regent of England in 1814, with a tourbillon clock mounted atop a bronze cone.

The Legacy & Continuations

A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon “Pour le Mérite”

After the passing of maestro himself, the tourbillon was still popular, especially in England, with notable companies making their own tourbillon timepieces. One such company was the Dent company, based in London. Dent is probably the most under-the-radar company there is, and yet it hides its most significant success in plain sight. I am, of course, referring to the clock inside the Elizabeth Tower in London, although most people call it Big Ben. Back to the tourbillon. Other makers took it upon themselves to create a tourbillon timepiece; one such was Girard Perregaux which created the Three Golden Bridges which was patented in 1884, a design they still use to this day.

The story of the tourbillon goes a little bit quiet after this, while it is still a marvel, times have changed. That was until Danish horologist Bahne Bonniksen brought the tourbillon back to centre stage, albeit with some changes and a new name, the karrusel (carrousel). Just like the tourbillon, the karrusel also rotates the balance assembly on its axis as it oscillates. This rotating therefore mitigates the effects gravity has on the performance of the watch, just like the tourbillon. The difference is that the karrusel uses a separate, second gear to move the cage around the balance. On Breguet’s tourbillon, the power for the balance and the rotating cage comes through the same point. Bonniksen’s karrusel simplifies this and also makes it a little more durable as well as less pressure is put on such tiny parts. It’s worth noting that Bonniksen’s karrusel watches were exceptionally well regarded because of their accuracy.

Blancpain L’Evolution Tourbillon Carrousel

The best example of both these mechanisms is Blancpain’s L’Evolution Tourbillon Carrousel watch, which features both of these unique complications as the name suggests. I got to wear this watch for a bit at an event held in the London boutique back in November, and I must say it was one hell of a beast, both proportionally and horologically. A couple of things to note, though. Blancpain is probably the only company with serial production of karrusel watches around. Also, Blancpain’s tourbillons look a little different from those of Breguet’s design. The balance still rotates on its axis, so it is still a tourbillon, but it’s in an anchor style assembly, which is lighter and easier to move than the traditional design which has a big cage around a large balance wheel.

At some point in history, the tourbillon made it into the wristwatch, around the mid-1940s with a watch made for Patek Philippe by an expert watchmaker. Omega also made tourbillon watches around this time and later, too.

Tourbillon Variants

Bulgari Octo Finissimo Tourbillon

In 1986, Audemars Piguet revealed the calibre 2870, the thinnest automatic tourbillon ever made. It was also the first automatic tourbillon and the first time said automatic tourbillon was placed inside a wristwatch. It remains groundbreaking to this day, although Breguet did strike back with the Classique Complications 5377 (and also the new 5367 coming in Baselworld this year), which has a 3mm thick movement, only 0.6mm thicker than AP’s 2870. The Classique Complications Tourbillon Extra-Plat collection garners the title of the world’s thinnest automatic tourbillon currently in production, though. However, the record for thinnest tourbillon ever made belongs to Bulgari with the 1.95mm thick Octo Finissimo Tourbillon, although it is manually wound instead.

Jaeger-LeCoultre Duomètre Sphérotourbillon

The tourbillon has also taken on more complexities over time, with extra axes and motions being the primary order. Jaeger-LeCoultre and Thomas Prescher have both made names for themselves with their 3D tourbillons. In these, they attempt to solve the problem faced by the classic tourbillon, that a wristwatch is not held vertical all day but moves around instead. In a 3D tourbillon, like Jaeger’s Gyrotourbillon and the weird but mesmerising Sphérotourbillon, the aim is to rotate the already rotating balance wheel, but it rotates on a different axis. It’s like a play within a play which is within another play; it’s all quite confusing. One would imagine that all this complexity does make a difference to accuracy, sadly we are not able to test this for ourselves, so who knows.

Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon 30° Asymétrique

One of the earliest inventions from elite independent Haute Horlogerie manufactures, Greubel Forsey, was a unique take on the tourbillon. Greubel Forsey’s Double Tourbillon system looks suspiciously like some 3D tourbillon. The inner tourbillon is inclined by 30 degrees, which explains the unusual angle seen. The outer tourbillon moves this inner tourbillon around. Because of this, the tourbillon never stays in one position, counteracting the positional effects of gravity, although this system is also very effective when the watch isn’t being worn. There are over 130 components required for the double tourbillon in a Greubel Forsey, that’s more than some entire movements.

Glashütte Original Senator Tourbillon Alfred Helwig

Lots of watches feature tourbillons, but not very many have what’s called a ‘Flying Tourbillon’. Unlike most tourbillons (like the Classique Complications 5377 for example), there is no upper bridge supporting the tourbillon, it is held in place only from below. Think of things like the Glashütte Original Senator Tourbillon Alfred Helwig, and it’s quite evident that there is no bar across the top to support the tourbillon. It is mentioned in another tourbillon article that the flying tourbillon was invented in England, by a man named Robert Benson North. Unlike Alfred Helwig’s design of flying tourbillon, the design from North featured a separate balance cock for the balance wheel and the tourbillon cage, which is why it appears not to be a flying tourbillon. Helwig’s design has all of that arranged underneath the tourbillon, and all of it is mounted on the same balance cock (or bridge in some cases).

Breguet Classique Complications 5347 Double Tourbillon

In recent times the king of tourbillons has returned to the throne, as Breguet makes a whole variety of tourbillon watches. These range from the very traditional to the highly technical such as is found in the Tradition 7047 which uses silicon components and a titanium cage to make the vast tourbillon very robust. They’ve also included the tourbillon with other complications, most notably minute repeaters, or in the case of my grail piece, another tourbillon, to make the Classique Complications 5347 Double Tourbillon. Considering that the tourbillon is considered a complication made by the serious horology players, it’s no wonder so many are on the market right now. Thanks to the ‘ahem’ innovations made by Chinese movement companies, the tourbillon is also becoming cheaper too. But, it is my personal opinion that our beloved whirlwind (the English word for tourbillon) will remain at the helm of complications, as every tourbillon watch made is a lesson in Abraham Louis Breguet’s absolute passion for accuracy above all else.